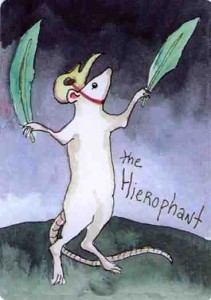

The illustration for the Hierophant commenced in a tiny cabin in Fairbanks, AK, in the midst of a love affair with Pan. Commonly known as the Greek god of wild places, shepherds and flocks, hunting, folk music, and seducer of nymphs, Pan’s origins are obscure and far older than the Olympic pantheon.

The illustration for the Hierophant commenced in a tiny cabin in Fairbanks, AK, in the midst of a love affair with Pan. Commonly known as the Greek god of wild places, shepherds and flocks, hunting, folk music, and seducer of nymphs, Pan’s origins are obscure and far older than the Olympic pantheon.

Gods exist due to our worship in one form or another. [See the moral from Dec. 6th 2013]. That which brings us closer to god— the Hierophant— is that which is able to increase our worship of god [See March 10, 2012]. My preferred form of worship is love, altho some seem to prefer fear. Thus, the illustration was to have been Pan and a nymph, which I’m sure some would have taken as devil worship. Really, the only way one can worship the devil is to place one’s self-pleasure above all else, which is what I’m supposed to have depicted in the Devil. Gods, on the other hand, take many forms. Some have crooked hairy legs and goat horns.

Although I was in love with Pan, I would have been quite happy to have been seduced by any god. Unfortunately, gods stayed away. Fortunately, muses abounded. Unfortunately, at least one of them was strong-headed. I had meant to depict the Hierophant as Pan and an adoring nymph. Somewhere along the line, my muse got ideas of her own and moved my hand to draw a bull-headed, bull-handed man reminiscent of the Minotaur.

The Minotaur is not one of many; thus, one cannot say, “a minotaur.” The Minotaur is a result of a bestial love affair between a snow-white bull and Minos’ wife Pasipha. King Minos was supposed to sacrifice the bull that Posiedon had given him, but Minos really, really liked that bull and decided to sacrifice one of his own in stead. Provoked to great annoyance, Posiedon caused Minos’ wife Pasipha fall in love with the bull. Pasipha hired Daedalus make a wooden cow for her to hide in. The bull was suitably duped— pacified, so to speak. Pasipha became pregnant. She birthed the Minotaur: the taurus (bull) of Minos, a terrifying and destructive monster. Daedalus was again called in, this time by King Minos who ordered him to design a gigantic, intricate and inescapable labyrinth in which to hide Minos’ own shame. For his efforts, Daedalus was rewarded with imprisonment, but that’s a whole other story.

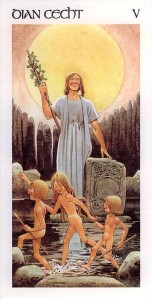

My point is, despite appearances, this is not the Minotaur. My misdirected muse caused me to draw a nice, loving holy man with the head of a sacred bull. I do rather like him, myself.