I did a woodcut print a number of years ago (to be posted in one week) called, “It was Raining Out.” In the image, a boy pulls a girl by the hand. He points to a ladder which leads to the attic. In the attic, there is a trunk. Outside, umbrellas fall like rain.

* * *

It is the attic, the endless attic where all toys go when they are outgrown, where the works of years past are laid to wait for the minds of future generations. There, the treasures are endless.

When it rains out, the boy and the girl sneak into the attic, close the door, and open an old wooden trunk, origin of all adventure. In the trunk lie the treasures of the mind, for it is filled with papers— letters, photographs, journals, cards— papers covered in writing and images.

One rainy day, the boy picks out a small carved wooden box. A box within a box. He opens it. Inside are slips of paper. On each piece, writ with fine fountain-pen script, is a terse aphorism: a riddle.

The girl takes the one on top and reads it aloud. “…”

“A riddle,” says the boy. “But what could it mean?” He takes the next, reads it. “…”

“I wonder how many there are” says the girl. She dumps the papers and arranges them in a grid on the floor to count. “Twenty-two.”

* * *

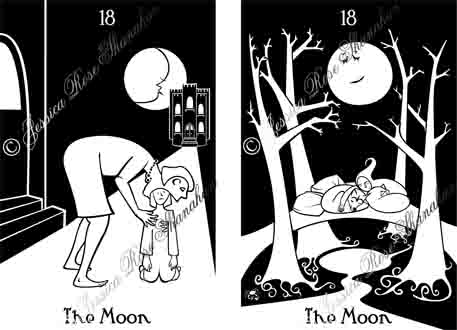

The problem was, I had no basis for filling in the ellipses. I had never seen a tarot deck. I knew there were twenty-two pictures. I knew there was a fool. I didn’t think the sixteen faces and forty numbers were actually part of the tarot deck. I had some research to do.

I went into a store that specialized in tarot decks and went through their albums of sample cards. Nothing caught my eye. They were all 78-card decks and none of them were special. At last I found a little hand-written booklet with a red lion on the cover and the words, “Twenty-Two Keys of the Tarot.” THIS was what I was looking for.

“Do you have the deck for this booklet?” I asked the clerk.

“It’s somewhere in the back,” he said, disappearing through a door beyond the bookshelves. When he returned, he handed me a small white box. “Just one,” he said. “It’s been here for ages. There’s no price on it.”

“May I look?” I asked. I was filled with that nervous sort of energy that happens when everything is absolutely right. It made my hands shake as I opened the box flap, and I was too jittery to see anything beyond the print quality (real ink on real paper) and the hand-written date. The deck was exactly 20 years old. “How much?” I asked.

“Name your price,” said the clerk.

“Ten dollars,” I said, knowing nothing about anything. I wasn’t the sort of person who bought things. The clerk nodded, rung me up, and slipped the deck into a small brown paper bag. I walked home, glowing brilliantly like the sun in the heavens.

In the spring of 1995, I was gently nudged towards the path of feminism by my then-boyfriend, a man who would be affectionately known as My Favorite Former Lover for years to come. He was a god in bed, and with his artist’s touch he sculpted women into goddesses. I was in college majoring in writing and biology— a double major due more to indecision than ambition— and one of my classes was ANT 280: Human Evolution. Our assignment was broad: pick a topic in human evolution and write about it. A biologist by nature, left to my own devices I would have probably found something nice and dry to write about, such as the correlation between spinal curvature and cranial capacity between years X and Y. As it was, newly introduced to the concepts of neo-paganism and sexy-feminism, I chose to write about neolithic society and religion in southeastern Europe.

In the spring of 1995, I was gently nudged towards the path of feminism by my then-boyfriend, a man who would be affectionately known as My Favorite Former Lover for years to come. He was a god in bed, and with his artist’s touch he sculpted women into goddesses. I was in college majoring in writing and biology— a double major due more to indecision than ambition— and one of my classes was ANT 280: Human Evolution. Our assignment was broad: pick a topic in human evolution and write about it. A biologist by nature, left to my own devices I would have probably found something nice and dry to write about, such as the correlation between spinal curvature and cranial capacity between years X and Y. As it was, newly introduced to the concepts of neo-paganism and sexy-feminism, I chose to write about neolithic society and religion in southeastern Europe.